The biologically important membrane proteins remain a challenging target for structural and functional studies, despite recent advances in biomolecular characterization capabilities. This is due to intrinsic difficulties in expressing, purifying and preparing membrane proteins for analysis while preserving their structure and activity.

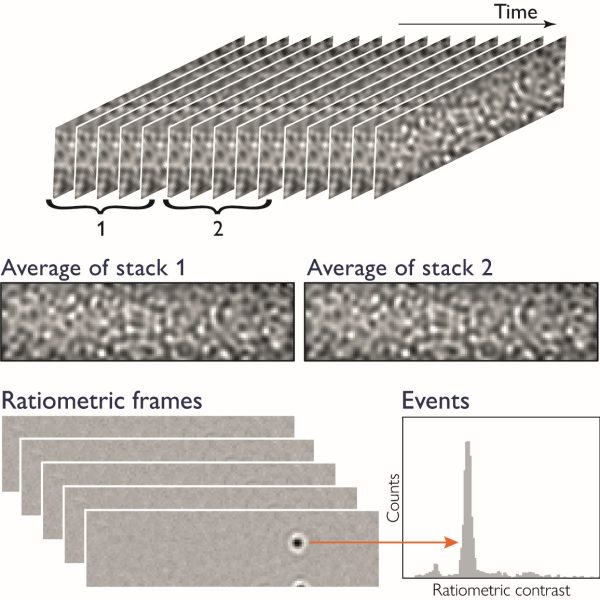

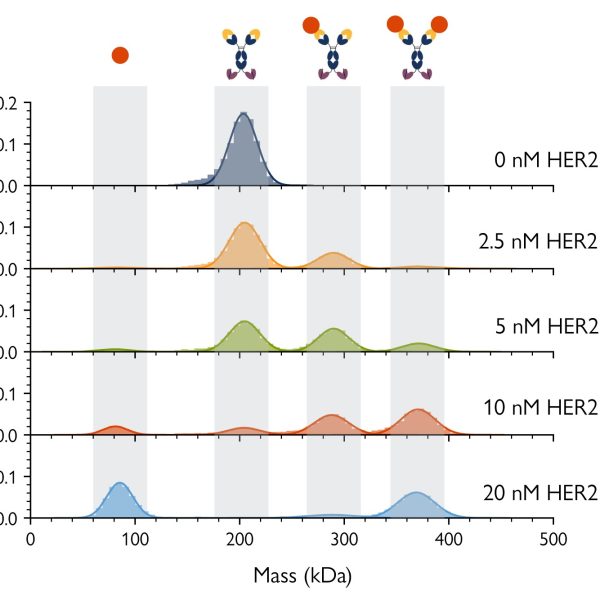

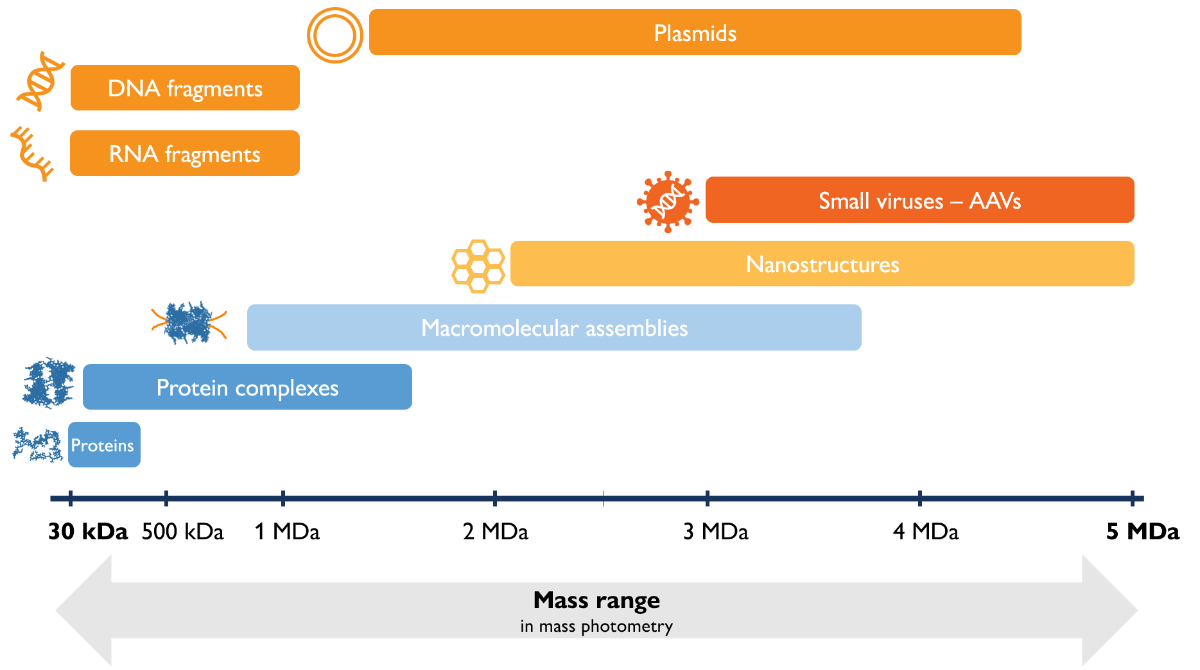

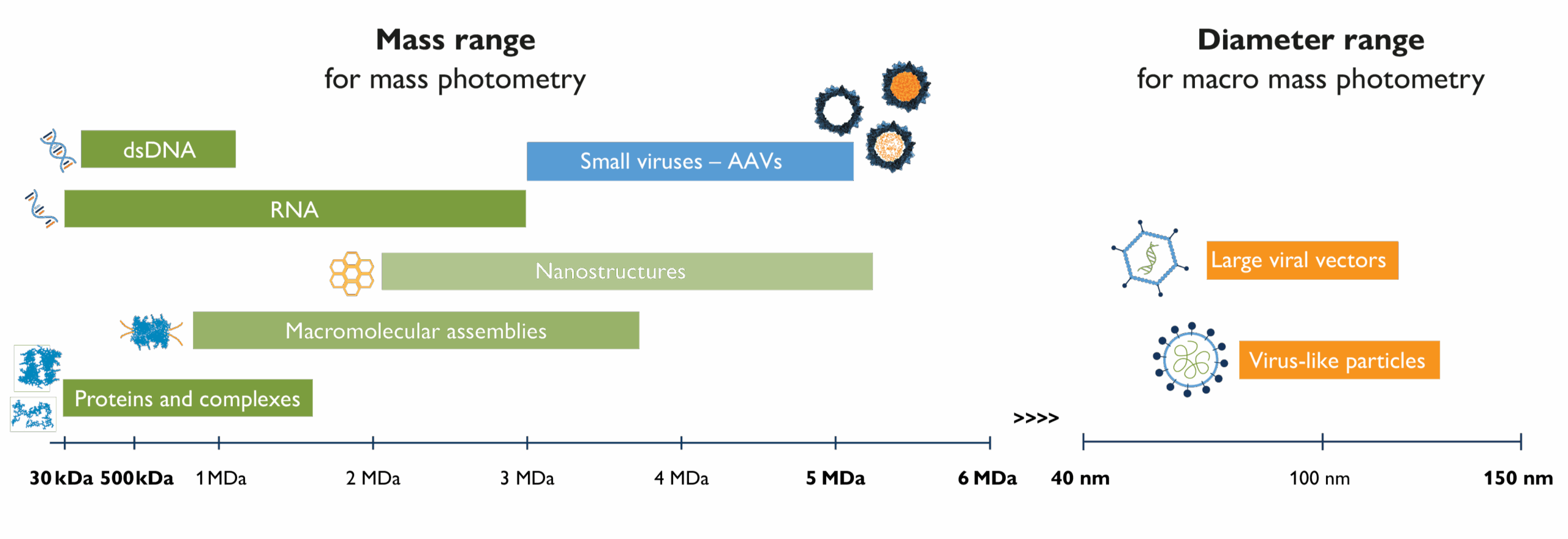

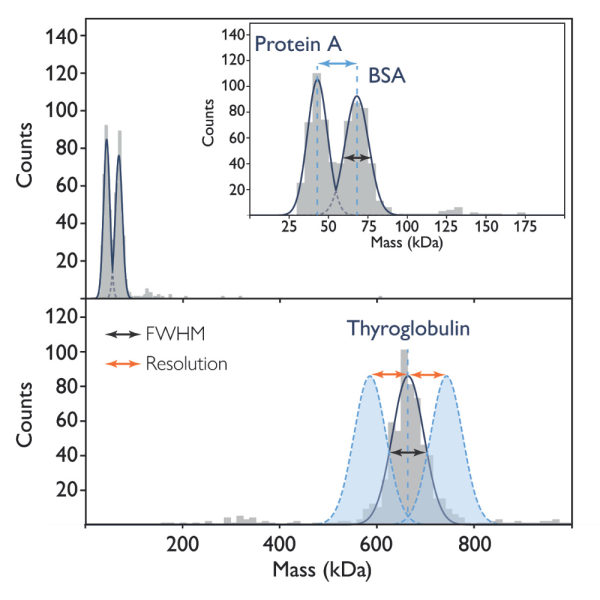

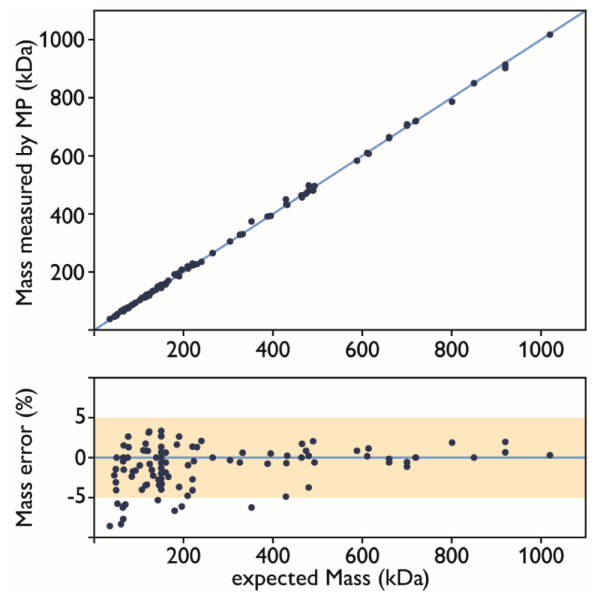

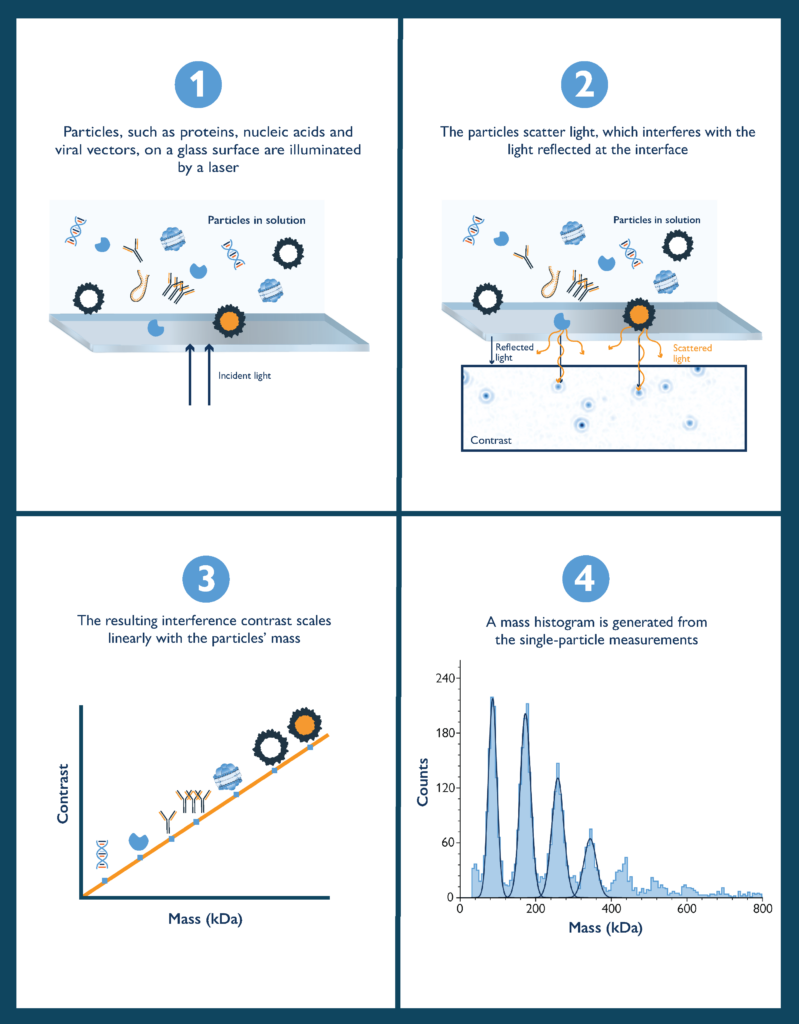

Mass photometry is a powerful biomolecular characterization technology that can help overcome these difficulties. Mass photometry provides high-resolution information on the mass distribution of particles in solution at the single-molecule level. It requires no labels and very little sample, and gives results in a matter of minutes.

Moreover, mass photometry can be used to measure samples with membrane mimetics [1], such as:

- Detergents

- Nanodiscs

- Styrene maleic acid lipid particles (SMALPs)

- Amphiphilic polymers (amphipols)

Mass photometry provides valuable information on the purity and behavior of samples containing membrane proteins and membrane mimetics, including:

- Aggregation, helping make sure membrane proteins are correctly solubilized

- Oligomerization state of solubilized membrane proteins under different experimental conditions

- Equilibrium states of two or more components in a sample

- Interaction dynamics

In this blog post, we examine the role of mass photometry in membrane protein analysis and describe case studies that illustrate how mass photometry is contributing to the field.

In case you’re interested in learning how mass photometry can help with your specific application, get in touch.

——————————

Outline

- Mass photometry and detergents

- Mass photometry and cryo-EM

- Mass photometry for nanodisc assessment

- Mass photometry and amphipols

- Outlook

- Further resources

- References

——————————

Mass photometry can be used to measure proteins in samples containing detergents. Mass photometry is a versatile and fast method, and experimental protocols can be adjusted to work around the noise introduced by detergent molecules and micelles. See the application notefor more details on how to use mass photometry to measure samples containing detergent and optimize your experimental conditions

——————————

Mass photometry and detergents

Working with detergents is notoriously difficult and represents a major obstacle in membrane protein characterization. Detergents increase sample heterogeneity and can have very different behaviors in slightly different experimental conditions. In addition, some analytical techniques are incompatible with the use of detergents.

Mass photometry is sensitive enough to measure proteins and protein-micelle complexes within detergent-containing samples and works in samples containing a wide variety of detergents and buffers. Moreover, its low time and sample requirements vastly reduce the cost of the unavoidable trial and error involved in using detergents.

An example showcasing the strengths of mass photometry for the study of membrane proteins in detergent can be found in a 2021 study by Paul Weiland and Florian Altegoer from the University of Marburg, which provided valuable insights about the membrane proteins involved in infection in the corn fungal pathogen Ustilago maydis [2]. U. maydis can have severe impacts on cereal crops and relies on specialized membrane proteins for the infection process, but little was known about the identities of those membrane proteins or how they worked.

Weiland and Altegoer screened six genes known to be upregulated in the fungus during infection of the host and identified two that significantly reduced virulence when deleted. They named the transmembrane proteins encoded by these two genes “Virulence-associated membrane proteins (Vmp) 1 and 2” and characterized them using a variety of methods, including mass photometry.

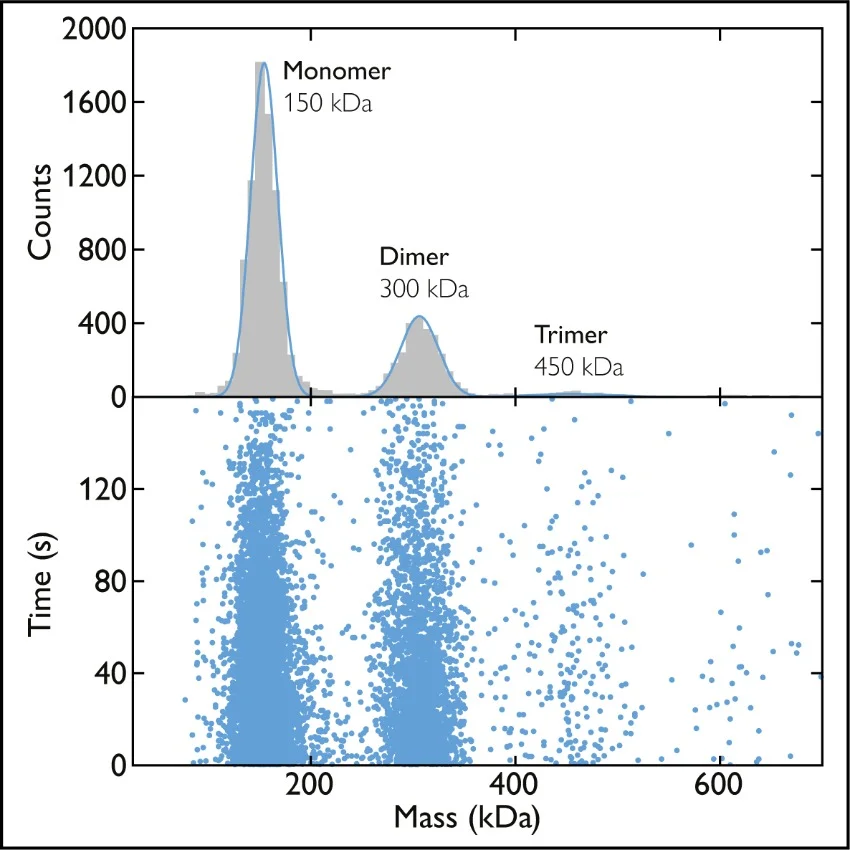

The authors used mass photometry to determine the oligomerization state of Vmp1 and Vmp2 in near-native conditions, using a fast in-drop dilution procedure to minimize the noise introduced by the detergents needed to solubilize them. Moreover, with mass photometry, they were able to measure the effects of different protein concentrations and detergent types on the oligomerization state of both proteins (Fig. 1).

The initial identification and characterization of two U. maydis proteins opens the way to further research on the infection process of this fungal pathogen. Mass photometry was a key part of the analysis, and this example demonstrates how it can be used as a standalone technique to extract information on membrane proteins and work around the complications that result from using detergents.

Fig. 1 Mass photometry measurements of U. maydis virulence-associated membrane proteins in detergent. Left plot shows the mass distribution for 25 nM Vmp1 samples solubilized in the detergent LDAO. A measured mass of close to 42 kDa suggests Vmp1 exists as monomers. Right plot shows the mass distribution of 100 nM Vmp2 samples solubilized in the detergent LDAO. A measured mass of 81 kDa indicates Vmp2 exists mainly as dimers. Adapted from figures 5 and 6 in [2].

——————————

Mass photometry and cryo-EM

Recent improvements in cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have allowed researchers to reconstruct the 3D structures of proteins in exquisite detail, going so far as ‘catching them in the act’ of performing their functions. However, even with cryo-EM, membrane proteins remain tricky to analyze. Finding the optimal detergents and their concentrations is critical for the success of experiments, but can turn into a time-consuming task that leaves one ‘waiting helplessly until the end of image processing to know if the optimization efforts have improved the situation or not’ [3].

Here is where mass photometry can help. As each measurement takes only a few minutes and little sample, it can be used to efficiently test different experimental conditions. We see an example in the first lecture of this webinar, where Dr. Oliver Clarke from Columbia University describes his team’s efforts to characterize the Ankyrin-1 membrane complex from red blood cells[TS1] [4].

The researchers’ aim was to obtain the structure of the Ankyrin-1 complex using cryo-EM. However, they first needed to find detergents that were compatible with purification and did not destabilize the complex. Mass photometry enabled them to identify the correct detergent for the analysis, which in this case was digitonin.

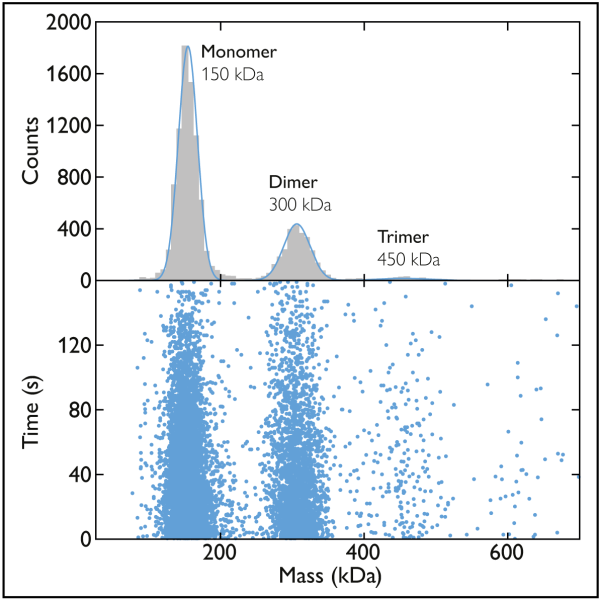

Mass photometry can be applied to samples containing nanodiscs. Thanks to its high sensitivity, mass photometry provides detailed information on the proportions of empty and full nanodiscs, as well as the oligomerization state of the protein within them. Moreover, a short measurement time speeds up the process of finding out which proportions of lipids, scaffold proteins and target proteins are optimal for sample preparation [1].

Another recent structural study further highlights the use of mass photometry within cryo-EM analytic pipelines. Beenken and colleagues [5] resolved the structure of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 2 –LRP2, also known as megalin – at extracellular and endosomal pH. The results revealed that the LRP2 is open to its ligand at extracellular pH but that its structure changes in response to endosomal pH, releasing the ligand. Such a system results in efficient ligand delivery and receptor recycling.

Beenken et al. used mass photometry in combination with sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation (SV-AUC) and SEC-MALS to examine the oligomeric state of LRP2. All three techniques gave similar results, showing a single population of particles of ≈ 1.2 MDa corresponding to stable LRP2 homodimers. The free detergent present in the sample was detected on mass histogram as a small population with low molecular weight, however it did not interfere with the LRP2 characterization.

——————————

Mass photometry for nanodisc assessment

In addition to detergents, membrane mimetics such as nanodiscs, SMALPs and amphipols are used to stabilize membrane proteins in solution for analysis. As with detergents, it is critical to find the optimal conditions for the experiment, and mass photometry can again help to expedite the process.

A clear demonstration of the use of mass photometry to evaluate nanodisc assembly and membrane protein integrity can be found in a recent study by Olerinyova and colleagues [1]. Here, the authors tested several sample preparations to integrate the potassium channel KcsA from Streptomyces lividans into nanodiscs.

Although two of the preparations had almost identical size exclusion chromatography (SEC) profiles, mass photometry revealed that KcsA was properly assembled into tetramers within the nanodiscs in only one of them. Functional analysis confirmed that only the preparation containing tetramers showed protein activity, demonstrating that mass photometry can provide critical information for nanodisc structural and functional studies that may not be available through other techniques.

——————————

Mass photometry and amphipols

Another use case of mass photometry can be found in a very interesting work by Webby et al. [6]. This paper looks at the organization of outer membrane proteins (OMPs) in E. coli. Using a combination of cross-linking assays and computer modeling, they determined that outer membrane proteins are not individually and randomly distributed over the membrane surface – the classical view. Instead, protein-lipid-protein interactions form large complexes that cover the membrane in a sort of lattice that serves as structural support.

Mass photometry was used to study complex formation between outer membrane proteins OmpF and BtuB, as their interaction did not survive native mass spectrometry analysis. Outer membrane proteins were solubilized using a detergent and, prior to mass photometry, they were transferred to amphipols. Mass photometry revealed that OmpF and BtuB form a heterogenous ensemble of complexes with different stoichiometries in solution.

——————————

Outlook

The case studies above show that mass photometry has an important role to play in the study of membrane proteins, either by itself or as part of a battery of analytical techniques. Structural biology, for instance, increasingly relies on multiple approaches working in tandem [5] and mass photometry will become an important component of biophysical analysis pipelines [6], [7]. Meanwhile, mass photometry and its applications continue to evolve, for example with the recent introduction of automated mass photometry. The emerging use of mass photometry for dynamic membrane protein tracking [8], [9] suggests that the technology’s applications in membrane protein analysis will further grow. More broadly, mass photometry’s versatility, speed and ease of use position it as a staple technology for membrane protein analysis.

——————————

Further resources:

To learn more about using mass photometry for the study of membrane proteins we recommend:

Blog – Mass photometry: a new way of characterizing biomolecules

Here you can learn about the basics of mass photometry and the main advantages it offers for the analysis of biomolecules.

Webinar – Investigating membrane protein complexes with mass photometry

This webinar is the source of two of the case studies presented. In the first talk, Dr. Oliver B. Clark, an assistant professor at Columbia University talks about his work on the structural characterization of the red blood cell Ankyrin-1 complex. He shows how mass photometry has helped find the optimal experimental conditions for Cryo-EM analysis of Ankyrin-1.

In the second talk, Dr. Andrea Saponaro, a PI at the University of Milan, explains his study of the structure of the HCN pacemaker and its interactions with regulators such as cAMP and TRIP8b. He talks about how mass photometry has helped determine the stoichiometry of the interaction between HCN1 and the full-length TRIP8b protein.

Webinar: Measuring Membrane Proteins with Mass-Sensitive Particle Tracking

In this webinar, Dr Nikolas Hundt (Ludwigs-Maximilian-University Munich), describes a new mass photometry strategy for tracking unlabeled molecules diffusing on supported lipid bilayers. With this approach, called mass-sensitive particle tracking (MSPT), researchers can determine the mass distributions and diffusion characteristics of membrane-associated protein complexes and observe protein assembly dynamics on a lipid interface in real time.

Application note: Mass photometry with detergents

This note describes in detail how to use mass photometry to measure samples containing detergents, including possible issues and workarounds.

——————————

References:

[1] A. Olerinyova et al., “Mass Photometry of Membrane Proteins”. Chem, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 224–236, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.11.011.

[2] P. Weiland and F. Altegoer, “Identification and Characterization of Two Transmembrane Proteins Required for Virulence of Ustilago maydis”. Frontiers in Plant Science, vol. 12, p. 669835, May 2021, doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.669835.

[3] Y. Cheng, “Membrane protein structural biology in the era of single particle cryo-EM”. Current opinion in structural biology, vol. 52, pp. 58–63, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.08.008.

[4] F. Vallese et al., “Architecture of the human erythrocyte ankyrin-1 complex”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 29, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1038/s41594-022-00792-w.

[5] A. Beenken et al., “Structures of LRP2 reveal a molecular machine for endocytosis.” Cell vol. 186, no. 4 p. 821 Feb. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.016.

[6] M. N. Webby et al., “Lipids mediate supramolecular outer membrane protein assembly in bacteria.” Science Advances vol. 8, no. 44 p. eadc9566, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adc9566.

[7] A. C. Steven and W. Baumeister, “The future is hybrid”. Journal of Structural Biology, vol. 163, no. 3, pp. 186–195, Sep. 2008, doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.06.002..

[8] S. Niebling et al., “Biophysical Screening Pipeline for Cryo-EM Grid Preparation of Membrane Proteins”. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, vol. 9, 2022, Accessed: Jul. 01, 2022. [Online]. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.882288

[9] Y. Xu and S. Dang, “Recent Technical Advances in Sample Preparation for Single-Particle Cryo-EM.” Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences vol. 9 Jun. 2022, doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.892459.

[10] E. D. B. Foley, M. S. Kushwah, G. Young, and P. Kukura, “Mass photometry enables label-free tracking and mass measurement of single proteins on lipid bilayers”. Nature Methods, vol. 18, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01261-w.

[11] T. Heermann, F. Steiert, B. Ramm, N. Hundt, and P. Schwille, “Mass-sensitive particle tracking to elucidate the membrane-associated MinDE reaction cycle”. Nature Methods, vol. 18, no. 10, pp. 1239–1246, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01260-x.